The number one mistake runners make in their training is training too hard. Beginners and veteran runners alike routinely make the mistake of doing too much, too often. I attribute this common mistake to a lack of awareness around running training intensity, and how to apply it to manage total training load.

Why Balancing Your Running Training Intensity is Important

The intensity at which you train and the duration of the session determine the load on your body. While running hard has a place in every training plan, overdoing it is a recipe for disaster. Running too fast, too often is the number one reason why runners have to learn how to handle a running injury.

A disproportionate amount of fast running is not a mistake limited to rookie runners. When you progress as a runner, it is easy to get caught up in your progress. You feel fit and robust, but before you know it, you have pushed too far and end up cross-training on the elliptical.

Train Slower to Become Faster

One common misconception resulting in people training too hard is the idea that you have to run fast to become fast. While training for a race should involve some running at goal race pace, that alone is not enough. Once you get to a particular volume, sticking to hard training alone is guaranteed to lead to injury.

In terms of physical load, running is quite taxing on the body. Even elite runners will tell you that the bulk of their training is at a low intensity. But, elites don’t just train at a low intensity because they can’t train hard all the time. They do it because it adds to their fitness. To illustrate why training variety is essential, let’s look at some simple charts.

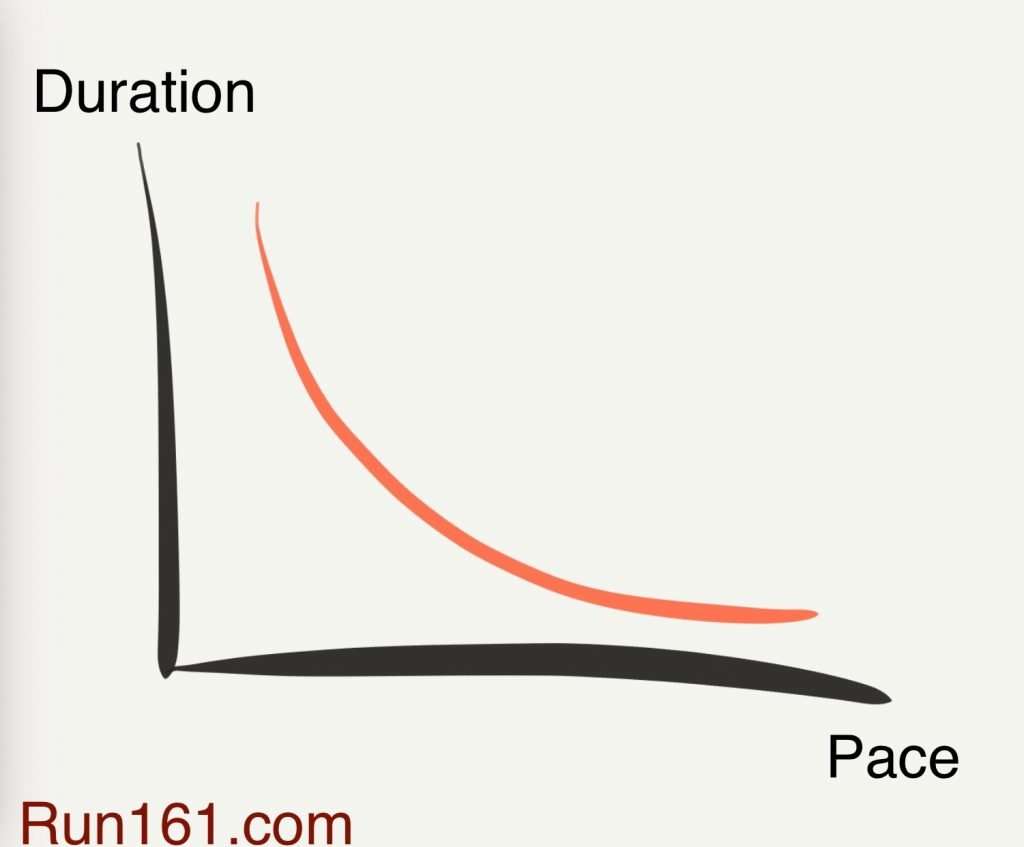

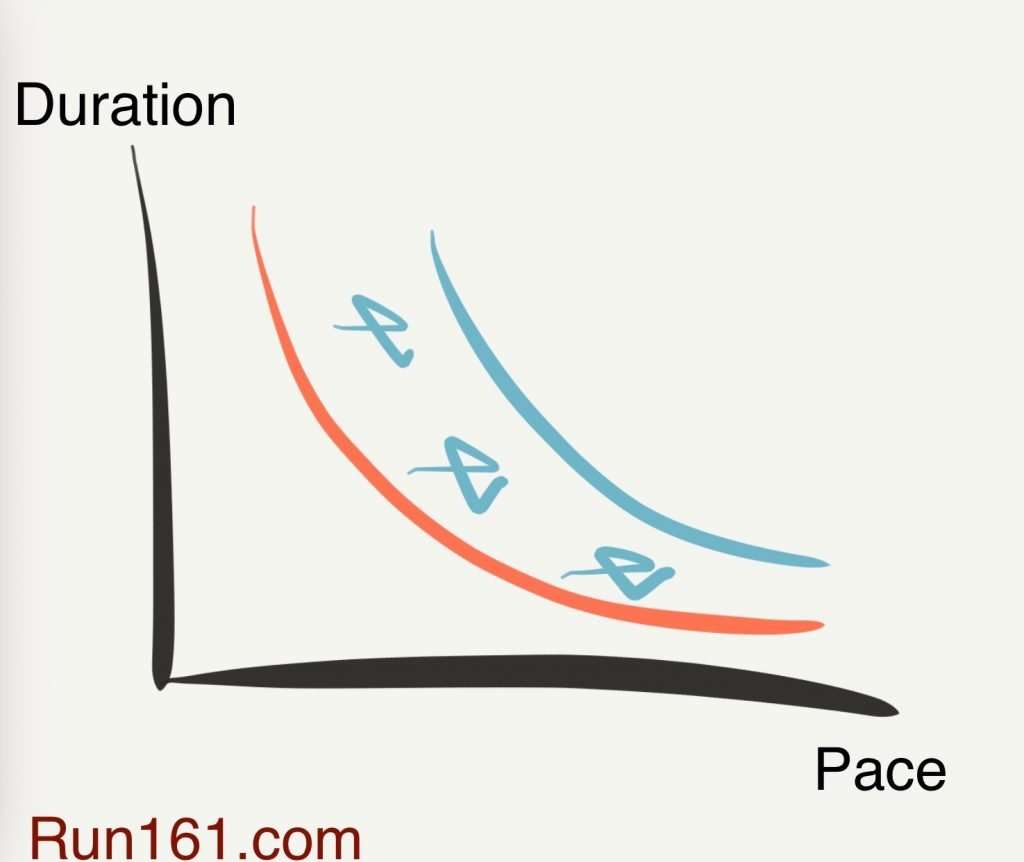

The Pace-Duration Relationship

The curve on this chart represents the relationship between pace (horizontal axis) and how long a runner can hold that pace (vertical axis). Each point on the curve also represents a particular combination of physiological duress placed on your body. That is to say, running at a slow pace which you can maintain for a long time gives a specific stimulus to the body. In turn, this stimulus results in a physiological adaption that improves the ability at this point on the curve.

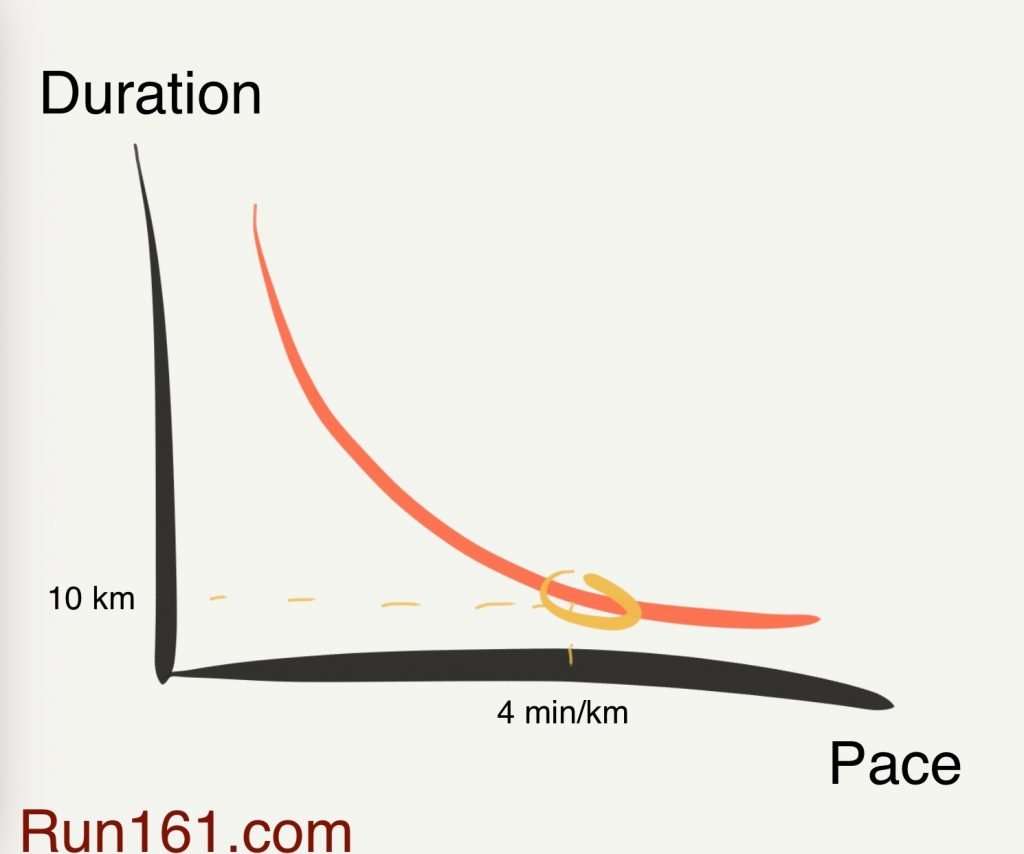

The highlighted point on the curve in the above illustration shows 4 min/km pace intersects with a duration of 10k. In other words, the curve represents a 40-minute 10k runner. Intuitively, this person may feel inclined to train as much as possible at paces on the right side of his current 10k pace. Indeed, this must be the best way to get better at the 10k?

It’s not.

Instead, we approach the task of becoming a faster runner by training at different intersections of our pace-duration curve.

Running training intensity theory specifies at which points on our pace-duration curve we should be training. There are several methods of defining and tracking your training intensity. I will come back to these later in the article. Likewise, there are many theories about how we should divide our running between the various effort levels.

The details of each distinct framework for intensity are not relevant here, however. What matters is that all of them agree on one point: The bulk of your training should be easy, and only a small portion of it should be hard.

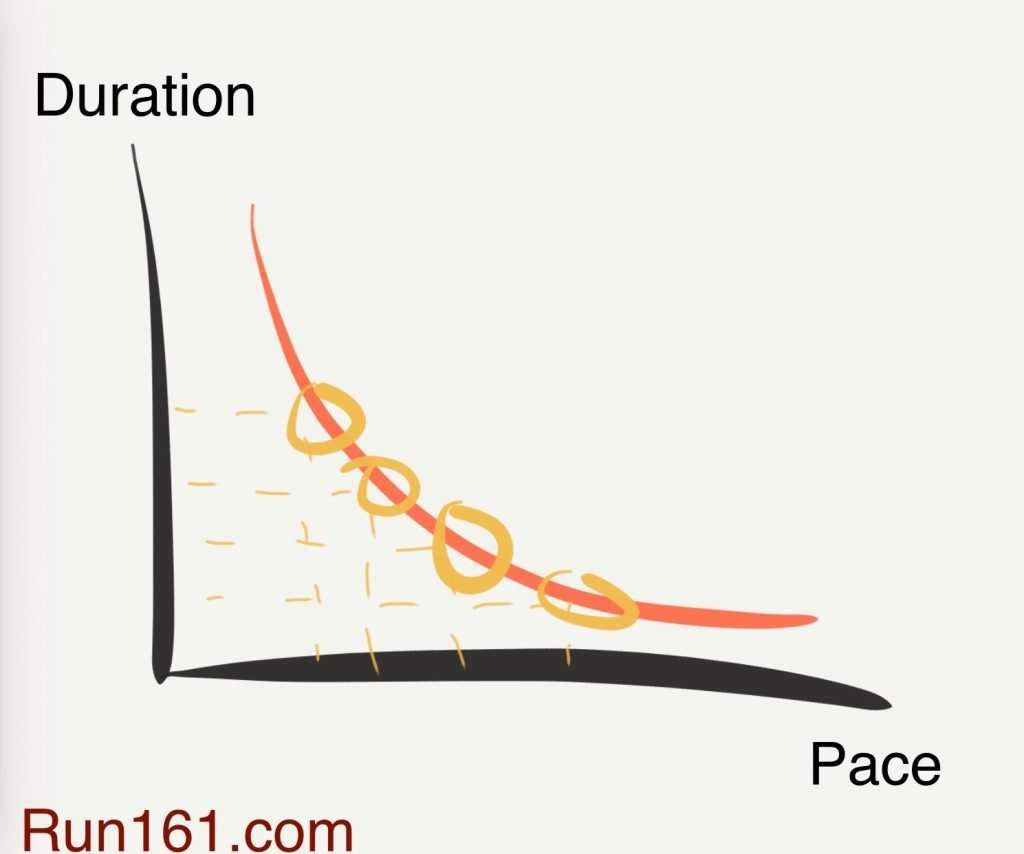

Shifting The Pace-Duration Curve

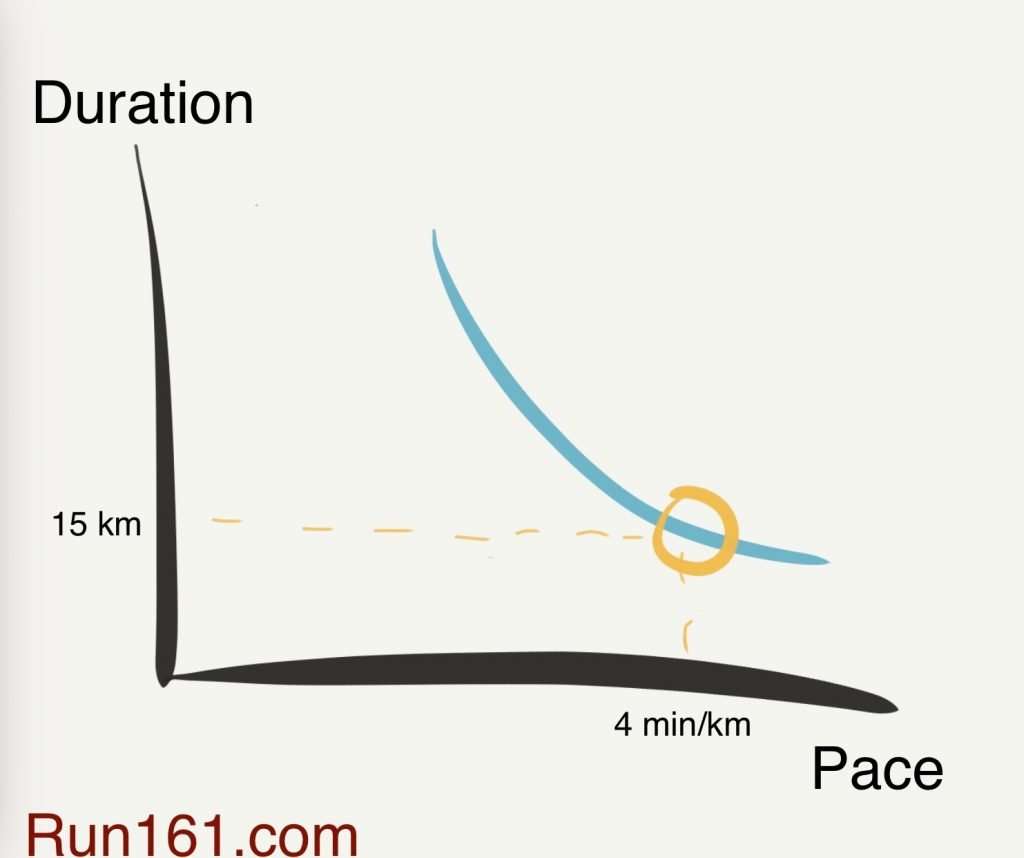

Let’s take another look at your pace-duration curve, and see how this will result in you becoming a faster 10k runner. By varying our training, we encourage our body to become more efficient across the spectrum. When this happens, the entire curve shifts to the right, as shown by the illustration below.

After a period of mixed training at various intensities, our former 40-minute 10k runner is now in much better shape. As shown below, his pace-duration curve has shifted to the right, and we see that he can now hold 4 min/km for up to 15 kilometres.

With a consistent and informed approach to running, you can improve your fitness. It takes time, and there are no short cuts or magic workouts that will do the trick. But the flip side is that this approach is sustainable, and over time, there will be an enormous improvement.

Methods of Measuring Running Training Intensity

To ensure that you are training correctly, you need an honest and reliable way to measure your intensity. There are several methods, all of which come with pros and cons.

Running by Feel

The easiest way to track your intensity while running is to run by feel. Got an easy run planned? Just make sure it feels comfortable. Is there a hard tempo run on the schedule? Go out and push it.

Running by feel is natural and straightforward, and works well for many runners. There are some drawbacks, however. Calibrating your body to the various intensities takes practice and experience. Almost every new runner end up running too hard if they try to run by feel. Likewise, hitting the right effort level during a hard session can be difficult without external pointers.

Pace

Another straight forward way to monitor your effort level is by pace. If you’re running on a track or a known distance, all you need is a watch. Get one with GPS functionality, and it will track mileage and continuously show your pace.

By using a race performance as a barometer for your fitness, you calculate the appropriate training intensities. One framework for doing this is Jack Daniels’ VDOT. I have used the VDOT system actively in my training with great success. It gives me confidence that I am running at the appropriate level going into hard sessions.

>> Further reading: Learn more about VDOT

While pace works well in most instances, there are some situations where it comes up short. Remember, your body doesn’t know the tempo of your run, only effort. When training in challenging conditions, it can be difficult to adjust paces to hit the right intensity zone. Likewise, residual fatigue and other life stress can make hitting goal paces more of a challenge than intended.

Heart Rate

Apart from a regular watch, heart rate monitors are by far the most popular external input to help runners gauge effort. While some sport watches can monitor your heart rate from your wrist, chest straps are still the gold standard for reliable readings.

By looking at how often your heart is beating relative to its max frequency, you can make sure you are training at the right intensity. I have found heart rate particularly eye-opening when it comes to easy runs. As I got started with running, I could not believe just how slow I should be going during my easy runs. But the heart rate monitor kept me honest.

Looking at my heart rate has also helped me during continuous threshold sessions. During these workouts, slowing down can be tempting because it feels hard. Keeping an eye on my heart rate, however, reassures me that I am doing what I should.

The biggest drawback of heart rate is that there can be a significant delay between effort increase and increased heart rate. The delay can be particularly troublesome as you run into uphills. Wrist-based heart rate monitors are also known to be unreliable, and prone to lock on to your cadence.

Running Power

Power meters have been a staple in cycling for a long time. When it comes to running, however, they have yet to gain mainstream adoption. There are several reasons for this, but the most important one is the fact that it is difficult to measure running power accurately.

However, a few signs currently indicate that running power might be gaining traction. Sport watch brands Polar and Garmin have both implemented power estimation in their recent gadgets. The foot pod power meters from Stryd can also be spotted frequently on the shoes of runners.

In theory, power should be a very efficient way to monitor your effort levels. Based on a power output test, you generate power zones to guide your training. Unlike pace and, to a certain extent, heart rate, power will help you adjust your effort when running up and downhills. Whereas heart rate has some delay, power is calculated instantly, so it works better in undulating terrain. Some power meters also account for wind resistance in their calculations, which makes it even more useful.

>> Further reading: Understanding Running Power: The Next Big Thing in Running Training?

I have tracked running power with my Garmin Fenix 5S and HRM-Run chest strap for more than a year now. The readings are usually consistent across laps and runs. However, the number of times I’ve seen significant differences in measured power output between even effort intervals makes me wary of relying on the measure. I do not have personal experiences with other running power meters.

Lactate Level

When it comes to measuring the effort during a hard workout accurately, lactate testing is the gold standard. When we run, our body produces lactate. The harder we run, the more lactate will flow through our bloodstream.

To measure lactate levels, you use a lactate meter. Immediately after an interval, you prick your finger to draw some blood. The lactate meter will then promptly calculate your blood lactate level.

In my experience, the rigorous process necessary to test lactate levels means that this method is quite limited in terms of use. However, it is quite popular in certain circles of elite runners for hard sessions on the track and treadmill. Similarly, it is the only reliable way to calculate your lactate threshold pace.

Running Training Intensity Designations

As already mentioned, there are many frameworks for determining training pace and intensity. In practice, you can combine a couple and present an argument for running at any given tempo. As with most things in running, what is important here is that you consistently, and over time, stick to certain principles in your training.

The following is not an exhaustive listing of the various terms used in training by runners everywhere. Instead, it is the set of running training intensity designations I have based my running around the past few years. Based on the theories of Jack Daniels and Pete Pfitzinger, I have improved immensely as a runner by keeping my running within these intensity zones.

Recovery

Separating recovery from easy running has been essential for my progress as a runner. I also believe it has helped me steer clear of significant injury problems.

The primary purpose of the recovery run is, as the name indicates, to promote recovery. Used after a hard workout and when you feel particularly beat up, the only thing that matters is to get your legs going, slowly. In terms of effort, it should be just one notch up from a brisk walk.

Beware, though, that because you are often exhausted when doing a recovery run, they will rarely feel that easy. Average heart rate for these runs should be around 70% of your max heart rate.

>> Further reading: Recovery Run — The Forgotten Running Intensity

Aerobic

Increasing aerobic capacity is probably the quickest way to improve for all but the most experienced runners. Enhanced aerobic capacity will help you shift your pace-duration curve, as illustrated above. Once your body gets used to regular running, it can handle a significant amount of running at this intensity.

Aerobic running should feel relaxed, and you should be comfortable in handling a conversation at this pace. Some days you will feel good, and it will be tempting to increase the tempo. Remember though, the purpose of these runs is to increase aerobic capacity without too much load. Save the harder running for workouts, and try to stick below 80% of your max heart rate here.

>> Further reading: Aerobic Running Improves Your Engine

Moderate

Steady running at around or a bit slower than your marathon pace has been a hot topic in recent years. Some argue that this is a black hole intensity, as research indicates that it is not optimal in terms of stimulating physiological adaptions.

While this may be true, there are mental and biomechanical benefits to getting used to running at race pace. One way to incorporate this intensity into your training plan is by progressing your long runs. Start by getting into the groove with a few easy miles, and then up the pace and end with a few miles at steady pace.

The way to describe this intensity would be comfortably hard. You can still hold a conversation but would prefer not to talk. Your heart rate should top out at around 85% of max.

>> Further reading: Moderate Running Builds Endurance and Strength

Threshold

A staple in the training program of any distance runner, the threshold sessions are crucial to becoming a faster runner. The name comes from the fact that these runs should take place at the intensity where the lactate in our blood accumulates at the same level as our body can clear them.

The most common definition of threshold pace is the tempo you can run in a 60-minute race. In practice, most runners look at their half marathon pace and try to keep their threshold efforts slightly faster. Heart rate will typically be around 85-90% during a threshold effort, and it feels quite challenging.

Threshold sessions can be split up into intervals, typically between 1000m – 6000m, with short breaks between. Alternatively, threshold workouts can be longer, continuous runs at threshold effort. In the case of the latter, these types of sessions are often referred to as tempo runs. Please note that the term tempo is a bit ambiguous, and people often have different meanings attached to it.

VO2 Max / Interval

In a traditional sense, the term interval running referred to these types of sessions where the intention is to improve your oxygen uptake. The way to achieve this is to spend time running right at the pace where your body takes up as much oxygen as possible. Running faster will place extra stress on your body without achieving the right training stimulus.

The most common definition of VO2 Max pace is your 3k to 5k race pace. For slower runners, however, this will be inaccurate. Instead, a 10 minute time trial can be helpful to determine the correct tempo for these intervals. A rule of thumb is that you should hit an effort level where you can run the first and the last repeat at the same pace.

Your perceived effort during these intervals should be high, and your heart rate can get as high as 95% of max. The rest period between the intervals should be significant to allow for adequate recovery. Somewhere between half and three-quarters of the duration of the interval is normal. Do not hesitate to go with equal rest, however, if you feel that you aren’t recovering well enough.

Repetition

Improving top-end speed requires a different approach compared to endurance work. Instead of trying to combine moderate paces with short rests, speedwork is all about running fast. And to run fast, you need sufficient recovery between each sprint. That means that each rep should feel no harder than the last.

You might think that because you are a distance runner, there is no sense in focusing on speedwork. The primary function of making reps a part of our training isn’t to become a fast sprinter. Instead, it helps improve form and running economy. In turn, better and more efficient running form translates to faster running across all paces.

When running repetitions, neither pace nor heart rate should be the primary concern. Instead, the focus should be all about combining fast running with a relaxed form. The moment you tighten up, and your gait is no longer relaxed, you are not doing it as prescribed.

Putting Running Training Intensity Theory Into Practice

If this seems complicated, don’t fret. At its core, running is a straightforward sport. The tools covered in this article are just that, tools. These tools are here to help give you confidence that you are training correctly and in a manner that will bring progress.

For those less interested in the finer details of training theory, though, the main takeaway from this should be the importance of switching up your training. With one or two hard runs per week, there is little that can go wrong if you stick to recovery and aerobic runs the rest of the week. Another common rule of thumb for adequately polarising your training is that 80% of your running should be comfortable, while 20% should be hard. Matt Fitzgerald popularized this concept with his book 80/20 Running.

If you do want to learn more about the finer details, however, I encourage you to explore further the terms and topics introduced here.

Like this?

Let me know by sending me an email at lc@run161.com.