Nearly three weeks have passed since I ran the Berlin Marathon. Actually, as it turns out, by the time I got to publishing this, four weeks had passed since the race.

I had been preparing for this race for the better part of a year. It had been the focus of all my training during that time. I had shared my journey in getting there with the world. It was supposed to be a momentous occasion. A celebration of a year’s worth of doing everything I could to run the marathon as fast as possible.

Instead, it was a train wreck. A grounded ship. An anticlimax of epic proportions.

It’s time to get over it, and move on. With this race report, my Running to Berlin journey comes to an end. Once this goes live, I never have to think about the 2022 Berlin Marathon ever again.

Or, maybe, just maybe, it marks the start of a shift in my mindset. A first step on the path towards being able to connect the dots. And, in doing so, feeling gratitude and appreciation for living through another challenging marathon.

Setting the Stage

Before getting to the race report in earnest, I want to offer some background information. I’ve documented my 18 weeks of training ahead of this race in needlessly detailed fashion through the Running to Berlin column.

What’s more, I’ve already shared the details of coming face to face with my existential demons during this race. Want to read about that aspect of the race? Check out this post, which contains an unedited draft written less than an hour after the race.

In this race report, therefore, I will be focusing on the last week leading up to the race, and the race itself–confronting existential dread notwithstanding.

Getting Ready to Race

Eight days out from the big race, I had my last bit of hard work on the plan. A 10k all out at the Oslo Maraton. That might seem a bit excessive so close to race day. Normally, I would agree. After I contracted covid ten weeks out from the race, however, I had to throw all my plans up in the air and start over again.

Covid hit me pretty hard. I missed three full weeks of training, and then spent two weeks slowly getting back into it. With no real sessions or long runs those two weeks, I essentially missed perhaps the five most crucial weeks of marathon preparations.

Black Swans, or Annoying Viruses

Plans are nothing, but planning is everything, as the old adage goes. So when you’re hit by something unexpected that you didn’t originally account for, it’s really just a chance to do some more planning. A chance to experiment, and to learn.

As I stood there with five weeks to go until race day, without having done any real marathon training for over a month, that particular mindset was hard to come by. But, regardless, I was eager to give it a go.

My new plan was to go hard for the next four weeks. But, to concentrate all my hard work into two big days. For these two days, the plan was to go both long and hard. Beyond that, I just wanted to fill up with as much easy mileage as possible. The reasoning for this was twofold:

- Having missed so many pivotal long runs, I needed to get in as much quality work as possible on tired legs. To try to get ready for the back half of the marathon.

- Getting as much exposure to marathon intensity as possible would help prepare me, both physically and mentally, for race day. When short on time, specificity is king.

And, I have to say, for nearly four weeks, that approach worked better than I had dared hope for. Although I was stretching myself to the limit, swerving close to race effort during my two hard days, my fitness recovered quickly.

Two weeks out from race day, I did a hard long run (Strava) with 7 times 2km on, 1km float. I did it on the track, to keep it flat–Berlin is very flat!–and to ensure I got accurate splits. After an extended warm-up, I finished that by covering a half marathon in 1:19:40. And I did it quite comfortably, running with the brakes on for a large part of it.

It renewed my hopes of challenging my personal best for the marathon–which stood at 2:39:34–two weeks later.

A 10k Fiasco

More than just going hard for four weeks, essentially reducing my taper to a single week, I wanted to try something else: To go for a “supercomp”. That is, do a very hard session quite close to race day, before taking it all the way down until the big race.

As always, the Oslo Maraton takes place eight days before Berlin. Which gave me the perfect opportunity to test this approach. So, I signed up, and went all out.

And when I say I went all out, I mean all out. I didn’t want to get too caught up in what the watch told me, because I probably wasn’t going to get close to my PB (34:11). But with no exposure to 10k pace for the past year, that was a bad idea. Because I no longer had any notion of what 10k pace actually feels like.

That’s how it came to pass that I ran the first kilometre of a 10k, with a fair amount of elevation gain, slightly faster than 3000 metre pace. Needless to say, that did not set me up for a good race experience.

I died a slow death, and by 3k I was finished. Then I held on for dear life, running around goal marathon pace for the next 4k. Surprisingly, I recovered quite well during that, and was able to muster up a decent finish, eventually crossing the finish line in 35:20.

It was probably a fair indication of my current ability. It indicates a marathon fitness around 2:45, perhaps a bit under. But, stubborn as I am, I didn’t let that stop me from thinking I was still in shape to challenge my personal best eight days later. Surely I could’ve run significantly faster with proper pacing, I told myself.

Shit Happens

In the days that followed, I felt like I was coming down with something. But, seeing as you always feel like that during a marathon taper (otherwise known as The Hypochondriac Phase of Marathon Training) I didn’t think much of it.

By Tuesday night, however, it became obvious that my immune system was under attack. I went to bed fearing the worst. My fears confirmed, I ended up spending the next 48 hours in said bed, extremely nauseous. I only got up for an occasional stride to reach the toilet in time.

I won’t go into further detail, but suffice it to say that this is not the ideal way to spend the last few days before a marathon. It was Thursday evening before I had the appetite to start eating again. Was there even a point in travelling to Berlin the next day?

Of course. You don’t put in all this work to forsake the opportunity to crown it with a race. Even if circumstances beyond your control means that you won’t get the race you were hoping for.

So as Friday rolled around, I made the trip to Berlin. Apart from a small trip to the expo, I spent the next 48 hours eating everything I could stomach, hoping to make up for those days hunched over the toilet.

Then came Sunday, and it was time to race.

The Race

As I jogged to the starting line, I couldn’t make up my mind on whether I was feeling completely terrible, or like a million bucks. It felt like a mix of both. Knowing what I do now, that turned out to be an accurate foreshadowing of what would come to pass over the next three hours.

Arriving at the start, I bumped into Eric. He’s a cool guy and great runner that I’ve gotten to know online, and it was nice to finally get a chance to meet him. My original plan had been to go out with Eric. However, because of how my week had unfolded, I told him that I’d just run to feel and see where it took me.

With minutes to go until the starting gun, there was a presentation of the main contenders in both the men’s and women’s race. Most of them got a polite applause. When Eliud Kipchoge stepped up, however, the many thousands of runners lined up and ready to race erupted into full fledged cheering. I got chills all over, and felt even more inspired to go out and race to the best of my abilities.

Flying

After being brought down by the stomach bug, I dropped all notions of racing for a time. Instead, my new ambition was to go out and run a beautiful race. To run within myself, and enjoy all the beautiful Berliners who came out to cheer us on. I wanted to take it all in, and give myself a chance to finish fast.

Starting in block A, I went out near the front. Eric went away from me quickly, as did hundreds of other runners. But I was determined to keep it controlled, and not let the occasion trick me into opening too fast.

After a mile or so, I settled into something resembling a group. I ran with no auto splits, and had only elapsed time showing on my watch. As such, I got no feedback on how fast I was running for the first few kilometres. The first pointer would be my first manual split while passing the 5k mark.

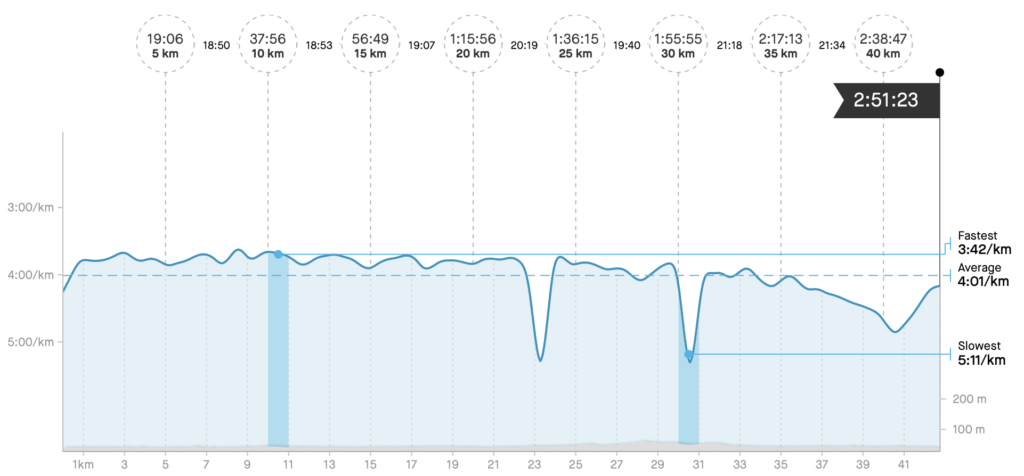

Without any feedback on how fast I was going, feel was all I had to go by. And I was feeling great! Passing the 5k marker in 19:14, I nearly fell out of my Vaporflys. For reference, that’s 2:42 pace, and it felt effortless.

I kept going, always letting my perceived effort guide my pace. At some points a few runners up ahead would glide away, and then I’d catch up again after a while without really trying. My next two 5k splits were 19:04 and 19:07.

Still, I felt so much in control that I couldn’t believe the splits I was seeing. Good signs!

Crashing

Approaching 20k, and eventually the halfway mark, the tide started turning. At around 18 kilometres, I felt some mild signs of cramping in my right calf. That’s weird, I thought. It’s not something I’ve experienced before in neither training nor racing.

It turned out to be another warning sign. Unlike Coldplay, though, at least I didn’t miss the good part.

I passed the half marathon in 1:20:50. At that point, I still genuinely believed that my personal best was in play. Then it all went downhill. Metaphorically, of course. Because, as I already mentioned, Berlin is pancake flat.

Something About the Shit and the Fan

Shortly after passing the half marathon, my stomach revolted. I knew I had to find a porta potty, and quickly. This has been an ongoing problem in my short running career. But, after discovering Maurten gels, I had no problems during my last two marathons. Nevertheless, here I found myself again. Thankfully, you’re never far away from a place to go out on the course in Berlin.

From my previous experiences, I know that rushing it is a bad choice in these circumstances. You’ll only end up going back shortly. So I spent more time on the porta potty than felt reasonable, hoping that this would be my first and only toilet stop. Around two minutes, to be exact.

Getting back out, I was overeager. I passed a lot of runners, thinking that I should be running faster than these people, trying to make up for lost time. With a 5k split between 20-25 kilometres of 21:03, that means–looking at running time alone–this was actually my fastest 5k split of the day.

That was a mistake.

The First Sparks of a Fire

Not long past 25 kilometres, it became clear that the struggle was on. I could feel my pace slipping. My gait became strained. Despite slowing down, I could no longer run in a relaxed manner.

Runners I’d passed over the past few kilometres came back and overtook me again. Mentally I found myself in a bit of a no-man’s land. I knew it was too early to start digging deep. Try to relax, I told myself. There’s still plenty of time to struggle.

Nearing the 30k mark, my stomach acted up once more. This time it came on in a more sudden fashion. I was worried I wouldn’t find a porta potty in time. But right after the 30k mark, a line of them appeared just up ahead.

Saved!

Once more, I did my business, and got out. But as soon as I started up again this time, I knew I was in big trouble. My legs were gone. Again, I’m speaking metaphorically.

Burning

Keep in mind, I still had no feedback on how fast I was running beyond every 5k mark. And that was a good thing. Looking at the data afterwards, I was able to keep up four minute kilometres (6:26/mile) until around 34 kilometres, when the implosion started in earnest.

I was entirely unprepared for what took place over the final eight kilometres. Although I’ve only run three marathons before, all three involved a certain degree of bonking. But never before have I experienced what took place here.

My pace slipping, I tried to dig in. But, unlike in previous marathons, I couldn’t muster up a response to stem the tide. I simply kept slowing. This brought on some pretty dark thoughts. Feelings of guilt, pointlessness, and loneliness washed over me, increasing in strength as my legs lost power, and my pace kept slowing.

To merely keep going took everything I had. All I wanted to do was to stop running, and start walking. There was just one thing. I have a rule:

Don’t quit.

Going into a race, I always decide on whether or not this is a day where I find out what I’m good for. And, if it is, that’s non-negotiable once the gun goes off. So I hobbled to the finish line, crossing it in 2:51:19.

Afterwards, I walked through Berlin’s Tiergarten and back to the hotel, devastated.

Again, if you want to know more about the emotional aspect of that final 10k, I shared the unedited words I wrote down an hour after crossing the finish line.

“Why do we fall, sir?”

After the race, my friend Carlos told me–and I like to believe that he did it in the wise voice of Michael Caine–that my struggle out there on the streets of Berlin will help me become a better marathoner. It’s hard to believe that in the midst of the disappointment of a race not going to plan. But I’ve since come to realise that it is true.

New experiences provide new references, and new opportunities to learn and grow.

What Went Wrong?

Despite all that, it seems pointless to spend too much time lingering on what went wrong this time around. What with that I missed out on five key weeks of training, and spent several days of the race week flat out/throwing up.

I’m fairly certain that I can ascribe my stomach problems to the bug I caught. With the risk of being too detailed, I hadn’t had a normal bowel movement for a week leading up to the race. I believe that my stomach simply wasn’t ready to handle the combination of a two day carb load, combined with fast running and gels.

It’s just the sort of thing you can’t account for.

Beyond that, missing out on important mileage and key long runs during the covid break obviously contributed. What’s what, I just can’t say. Could I have run a decent race if I’d avoided the stomach bug? Maybe, but after my experience in the final 10k, I’m convinced that I wouldn’t have come close to challenging my PB.

My best guess is that I would’ve died a slow death–because the first half would’ve been more or less identical either way–and finished in around 2:45. Give or take a minute or two.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I’m not done.

Running will remain an important part of my life until the day I check out, that much I know. But chasing times, and striving to run faster, is a demanding pursuit. So I have this vision of a different running me in the future. A me that’s just running for enjoyment and the myriad of benefits to my health and wellness.

Towards the end of the race, I thought it was time for that. But mere hours, if not just minutes, later, I knew that it was not time for that.

It’s not so much the time itself. If I “retire” with a 2:39 personal best, I’ll actually be happy with it. It’s just that the pursuit of improvement is so damned addictive, and I’m nowhere near ready to let it go. Perhaps I never will be.

So I will keep running. And I will do what I can to become a faster runner. With the constraints that come along with being a dad to two small kids, and not wanting them to pay the price for my personal, egotistical pursuits.

Which means you’ll see me running to and from work. …

Let me know by sending me an email at lc@run161.com.Like this?