While most of us stomp around, doing our best to gain some forward momentum, some runners appear to glide forward. You’d be forgiven for questioning whether their feet actually touch the ground, or provide propulsion by some sort of sorcery.

What is it that separates the stompers from the gliders? Is there a magic number that encapsulates the difference? And are there ways we can work on improving this number, and become faster, more efficient runners?

Defining Ground Contact Time

When we’re running, our feet touch the ground. Groundbreaking, I know, but bear with me. Every time our feet hit the ground, they linger there for a short while. The duration of our foot’s contact with the surface during each step is referred to ground contact time. It is typically expressed in milliseconds.

This metric has been studied in scientific environments for decades. The emergence of consumer grade wearable technology has, however, brought this number more attention in recent years.

Estimating Ground Contact Time

In previous times you needed expensive, specialised technology to estimate ground contact time. In contrast, today all you need is a smart watch such as a Garmin Forerunner 265 or an Apple Watch.

Here are some of the methods for estimating ground contact time.

Force Plate Treadmills

A physical exercise research lab is typically equipped with advanced treadmills. These treadmills are normally constructed to measure foot strike force. In addition to estimating running power, these force plates also allow us to infer ground contact time. It merely measures the time from when the foot hits the plate, until the force drops to zero.

The pros of this method is that it is highly accurate. And a force plated treadmill allows for continuous data capture.

The cons, however, is that it is expensive and requires a controlled setting. Plus running on a treadmill is not fully applicable to overground running.

High-Speed Camera and Video Analysis

Another in-lab option is to use high speed cameras. Using dedicated software to analyse the footage, we can get reliable estimates for parameters such as ground contact time.

A pro of this approach is that the visual representation allows for capturing additional biomechanical data. This can provide more context for the ground contact time estimate.

Cons are obviously that capturing footage requires you to run on a treadmill, and the need for highly specialised software.

In-shoe Equipment

Another option is insoles equipped with various technologies to capture data from your strides. Using pressure sensors, they can detect how much, and for how long your foot applies force to the ground.

Compared to previously mentioned options, this is a fully portable option. What’s more, it can be used to capture data during your ordinary runs.

The drawback is that the different shapes of your selection of running shoes can affect comfort and accuracy.

Watches and Footpods

Let’s be honest, we wouldn’t be talking about ground contact time if it wasn’t for the explosive development within this particular category. While it would’ve seemed like science fiction mere years ago, most state of the art sports watches can now estimate — with the help of tech such as accelerometers and advanced algorithms — your ground contact time with a decent degree of accuracy.

Want higher precision? No worries. Just add a bog standard heart rate strap from Garmin to your setup, and you’ll get even more accurate estimates. And, if you believe the sales pitch, a Stryd footpod will provide even more accurate data. (I’ve tested both of these extensively. My experience is that they track fairly similarly. Both in terms of absolute values, as well as relative to each other.)

How Ground Contact Time Affects Your Running

Let’s start by getting the obvious out of the way: The less time you spend on the ground, the more time you spend in flight. In other words, less ground contact time should, all other things equal, mean faster running.

And there is research to back up this assumption. For example a study from 2012 looking into the mechanics of sprint performance. 1Morin JB, Bourdin M, Edouard P, Peyrot N, Samozino P, Lacour JR. Mechanical determinants of 100-m sprint running performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 Nov;112(11):3921-30. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2379-8. Epub 2012 Mar 16. PMID: 22422028 Morin, et al. found that one of the main mechanical determinants of 100 metre sprinting performance was “a higher step frequency resulting from a shorter contact time”.

More recently, a paperfrom 2021 reached similar conclusions. Mooses, et al. found in their study conducted on female runners from Kenya 2Mooses M, Haile DW, Ojiambo R, Sang M, Mooses K, Lane AR, Hackney AC. Shorter Ground Contact Time and Better Running Economy: Evidence From Female Kenyan Runners. J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Feb 1;35(2):481-486. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002669. PMID: 29952871 that ground contact time was significantly correlated with running economy. And, by extension, that shorter ground contact time resulted in improved running economy.

What’s a Good Ground Contact Time?

To my knowledge, there has been no large scale research study dedicated to answering this particular question. Which is to say, we don’t really know if one particular number is better than another. Intuitively, we can surmise that less is better.

But, we don’t want to reduce ground contact time at the expense of efficiency. The aim while striking the ground is to produce forward momentum. In theory, there could be an ideal relationship between ground contact time and force generation for maximum efficiency, at which point further reducing ground contact time would reduce efficiency.

In a study from 2012, Chapman, et al. observed elite runners to look at ground contact time as an indicator of metabolic costs. 3Chapman RF, Laymon AS, Wilhite DP, McKenzie JM, Tanner DA, Stager JM. Ground contact time as an indicator of metabolic cost in elite distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 May;44(5):917-25. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182400520. PMID: 22089481 In terms of raw numbers, they found that the elite runners had a mean ground contact time around 155 ms. when running at a comfortably fast pace.

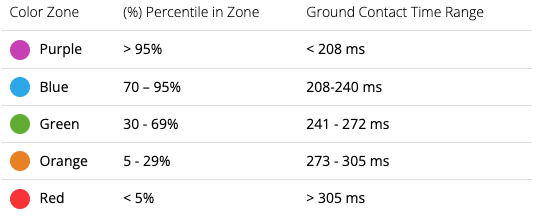

Garmin, the fitness and wearable company, no doubt has much data on hand here. And this is how they bucket the numbers while presenting a user’s ground contact time numbers:

So, according to Garmin, if your ground contact time is down towards or below 200 ms, you’re in the 95th percentile. It makes sense, then, that elite runners are showing numbers as low as 155 ms. One caveat here is that these numbers are not necessarily directly comparable. In the study, they used a high-speed video camera (250 fps) and analysed the footage to determine ground contact time. Whereas Garmin’s numbers are estimated either by a watch, or a centred heart rate strap.

Either way, based on Garmin’s numbers, we can make the following rules of thumb for ground contact time:

- < 210 ms: Great

- 210 – 240 ms: Good

- 241 – 270 ms: Room for improvement

- 271 – 300 ms: Needs improvement

- > 300 ms: Lots to work on

Of course, it is important to remember that these are generalised rules of thumbs. They are not hard limits that apply to everyone. And, as we’ll touch on in the next part of the article, ground contact time is closely related to other running dynamics metrics.

Ways to Improve Ground Contact Time

Before we look at steps to potentially improve ground contact time, it is important to understand that this number does not exist in isolation. It is closely tied to other metrics that describe your running biomechanics.

Numbers such as cadence, or step rate, and vertical oscillation are intricately connected to your ground contact time. As is the concept of ground contact time imbalance, which I’ve written about at length.

Identifying potential causes for injury aside, all of these numbers are only valuable to the extent that they help us measure, understand, and hopefully improve our running efficiency. And the number one way of improving your running efficiency? To run more.

That’s right. If your ground contact time numbers are not within the recommended range, the best step you can take is to run more. If you’re not running regularly, just doing so will lead to vast improvements.

Beyond that, however, there are certain ways to work on improving this metric. Which, in turn, should help you run more efficiently. Let’s take a look at the various approaches.

Methods for Improving Ground Contact Time

Strengthen Core and Hip

When your hip collapses in on itself while running, you spend more time on the ground. As such, one of the most straightforward ways to reduce ground contact time is to strengthen your hip and core. Of course, this is not something that’s done in a week, or a month.

There’s no quick fix when it comes to this point. You need to do the work to strengthen your hip and core. Through targeted strength work, such as plyometrics and with weights. Drills, such as high knees and butt kicks, is another good way to activate your hips. And, lastly, a variety of hill work can achieve much of the same. Whether that’s hill sprints, or focused exercises such as one and two leg jumps.

Focus on Arm Swing

Your arm carriage is an important factor in determining ground contact time. How you move your arms while running plays a role in maintaining balance and providing forward momentum. If your arm swing is inefficient, it can result in unnecessary motion in your torso. Which, in turn, will make it hard to keep your hips up, and reduce how quickly you can create power in the toe-off.

Increasing Cadence

I’ve already mentioned that there’s a close relationship between cadence and ground contact time. A low cadence increases the chances of overstriding. Overstriding, which means landing with your foot too far ahead of your centre of gravity, directly leads to increased ground contact time.

While your running friend may have claimed otherwise, there’s no gold standard for cadence. Your ideal step rate will depend on a variety of factors related to your physical makeup. Plus, cadence will naturally vary with pace. For this reason, I usually tell runners not to worry too much about their cadence number.

Instead, you should identify whether you’re actually overstriding. Because then, and only then, does it make sense to actively work on changing your cadence.

Ques for Minimising Ground Contact Time

In addition to working on the points above, you can use mental ques while running to improve your ground contact time. These are visualisations that you keep top of mind while running, in an attempt to improve your form.

Here, you should pick one that appeals to you, and work on it over time. You’re looking for a feeling, and the idea is to chase the movement that lets you experience that feeling. Over time, it will become second nature. Too much conscious thinking about how you’re running, however, rarely works well.

So pick one, and work towards it over time.

Landing and Toe-off as a Single Motion

My favourite way of visualising your running in a way that minimises ground contact time comes from Filip Ingebrigtsen. The 1500 metre World Championship bronze medalist from London in 2017 has one of the most aesthetically pleasing running forms of all top track runners. And in a Norwegian podcast, he shared his favourite visualisation for achieving it:

“I like to say that you should think about landing and toe-off in the same phase. It can be difficult to think your way to good technique, but you can (find it through) a feeling.”

I agree with Filip wholeheartedly here. And visualising landing and toe-off as a single, unified, and fluid motion can help you get there.

Staying Light on Your Feet

Another cue that can be effective is to visualise yourself as being light on your feet. While that may seem impossible as you’re slogging away, working hard to even go, it can help. Even something as concrete as imagining that you’re running on hot coals can help you get there.

Engaged Core and Hips

In the previous section, I noted that a strong core and hip helps reduce ground contact time. You can use this as a point of focus while running, too. Concentrate on activating your core, and keeping your hip joint high.

Active Push Off

One last que to use is focusing specifically on the toe-off. Instead of just lifting your foot, be conscious about actively pushing off with each step. This will help you generate more force, and ultimately reduce the time your feet linger on the ground.

Closing words

Ground contact time is just one of several biomechanical metrics that speak to your running efficiency. While there are ways to work on it, and actively try to reduce this metric, one important point remains:

Unless you’re struggling with injuries, the best way to improve your running economy is to run regularly. And if you’re running regularly, it is to run more. But, in certain cases, it can make sense to focus on improving this particular metric.

Like this?

Let me know by sending me an email at lc@run161.com.