To become a faster runner, you need to improve your aerobic capacity. How do you improve your aerobic capacity? By running at an easy to moderate pace, frequently and with consistency over time.

There are no short cuts or special tricks, no magic workouts that will get you there faster. Your aerobic capacity is, and will always be, a product of the work you do across years.

Aerobic and Anaerobic Running

To understand why aerobic running is such an essential component of running fitness, we must first understand what aerobic running is. Further, we must also learn about aerobic running’s counterpart, anaerobic running. To help explain, I am going to fall back on my extraordinary illustrative abilities.

A Tale of Two Energy Systems

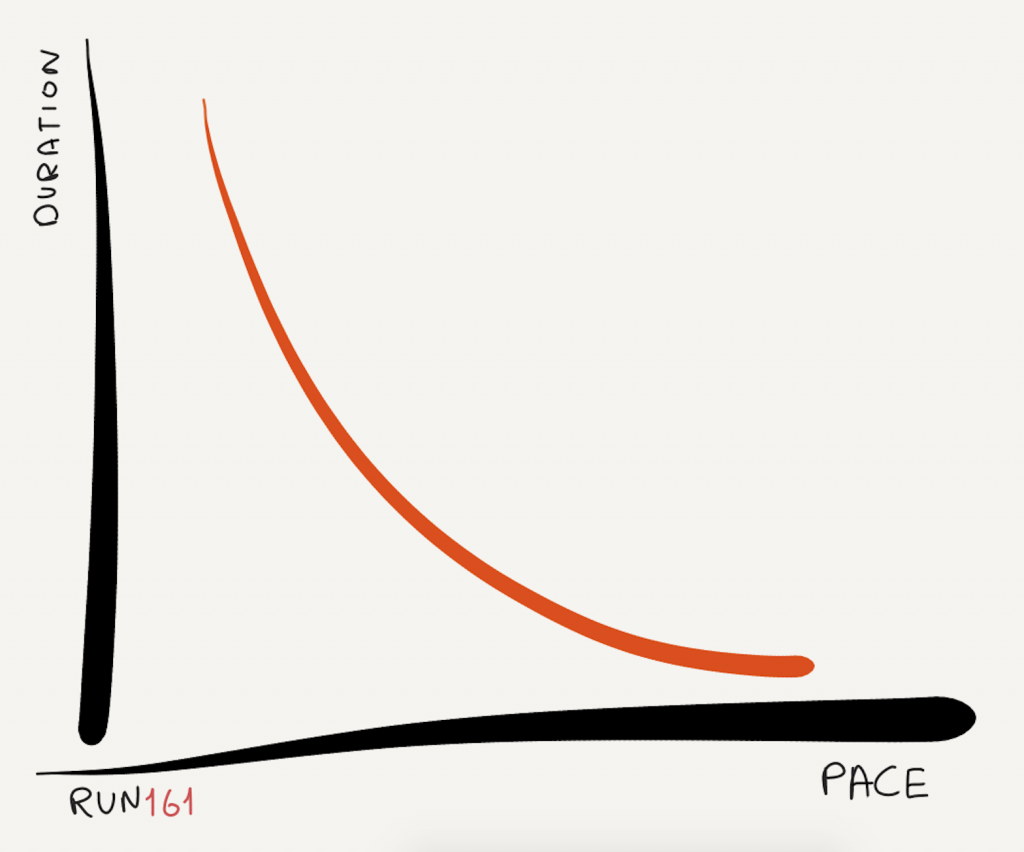

In the introduction to running training intensity, we became acquainted with the pace-duration curve. In case you need a refresher, this curve represents a particular runner’s relationship between a distinct pace and how long the runner can maintain that pace.

When we run, our bodies consume energy to keep us moving. Running is one of the most demanding forms of endurance exercise in terms of energy spend per minute of activity.

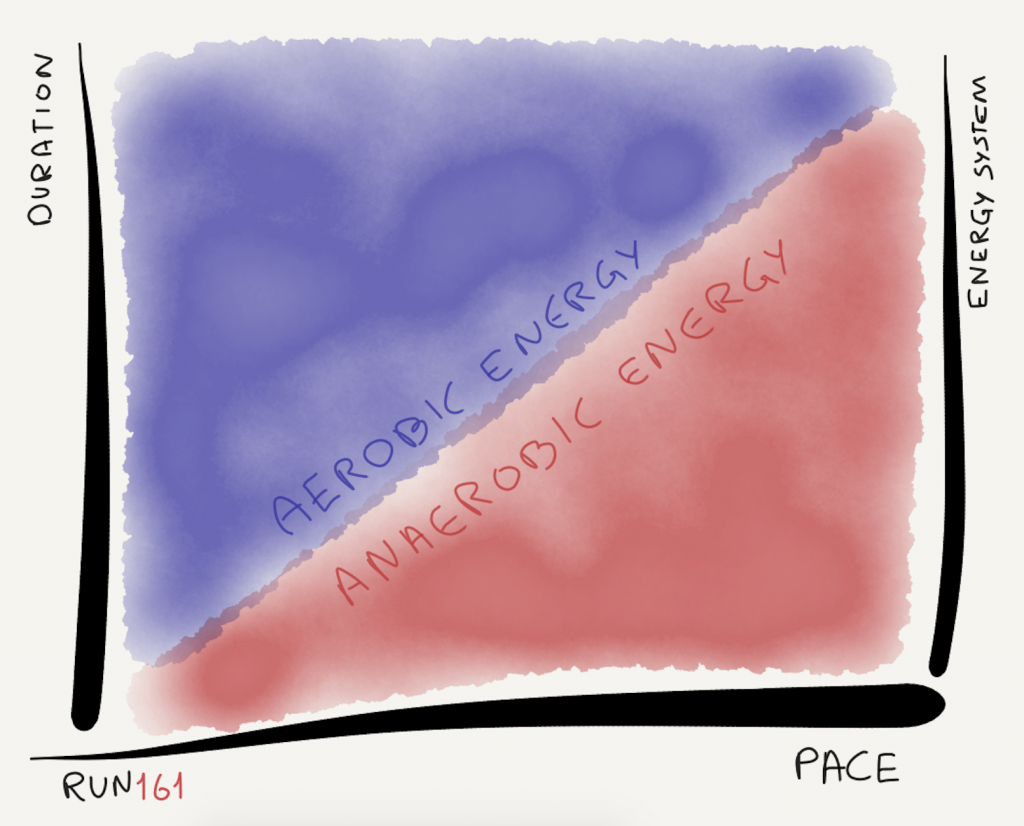

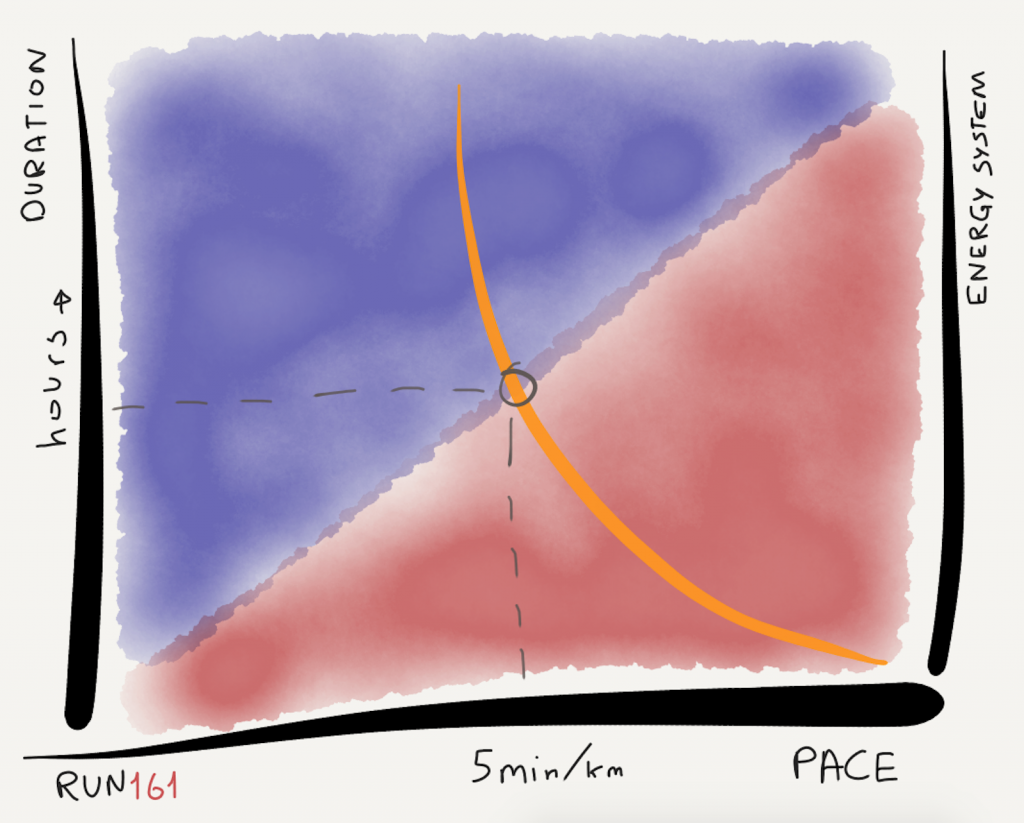

Our bodies have two distinct solutions to find the necessary energy to keep us going. These two systems are called the aerobic and the anaerobic energy systems. We can illustrate this by adding another dimension to the y-axis of our chart.

Regardless of how fast we run, we are always using both aerobic and anaerobic energy. As we run faster, a more significant portion of our total energy expenditure comes from the red part. That is the anaerobic energy system.

As we can deduce from this, the aerobic system is for slower running at lower intensities. Anaerobic running, then, must be for faster running. While the names of these two energy systems might seem nonsensical, the names reveal the key differences. Aerobic means “with oxygen” or “in the presence of oxygen” while anaerobic means “without oxygen.“

In simplified terms, that is the primary difference between the two energy systems. The aerobic energy system is slow and requires generous amounts of oxygen to oxidate the fatty acids stored in our bodies to fuel our activity. Conversely, the anaerobic energy system relies upon energy stored as carbohydrates, the figurative rocket fuel in our bodies. •••Fuel Choice During Exercise Is Determined by Intensity and Duration of Activity

How Aerobic Running Improves Your Engine

The physiological effects of running at an aerobic effort level are numerous, and these adaptions are crucial to your improvement as a runner.

Increase Capillary Count

Our bodies utilise capillaries to transport oxygen and remove waste products to and from the muscles. These are the smallest blood vessels in our bodies. During exercise, the number of capillaries surrounding the appropriate muscles determines the capacity to supply the muscle with oxygen and discharge waste.

In other words, the number of capillaries is an essential factor in determining your aerobic capacity. When you train at an aerobic intensity level, you stimulate the body to increase the number of capillaries during recovery.

Increase Mitochondrial Density

With oxygen in place, the mitochondria can work their magic. A part of the muscle cell, the mitochondria use oxygen to convert nutrients stored in your body into the energy that will keep you going. And going, and going.

Aerobic training spurs the growth of existing mitochondria and stimulates the production of additional “power factories” within your muscles. And the result, of course, is that you can produce more energy to run faster and longer.

Increase Myoglobin Amounts

While the capillaries bring the oxygen, and the mitochondria utilise it, a protein in the muscle cells negotiates the transfer of oxygen between the two. The name of this protein is myoglobin.

More considerable amounts of myoglobin in their muscles explain how diving mammals such as whales can stay submerged underwater for extended periods before coming back up for water.

Aerobic conditioning won’t give you the deep-diving abilities of a whale. It will, however, increase the amounts of myoglobin in your muscles. And, in turn, boost your endurance and make you a more durable runner.

While there are other physiological mechanisms involved in the process, these are the three main factors that determine your aerobic capacity.

Aerobic Capacity Is Important for All Distance Races

Unless you are a sprinter, your aerobic capacity is an essential factor in determining how fast you can run a given distance. A study published in 2005 by Duffield, Dawson and Goodman looked at the aerobic energy contribution in runners racing 1500 and 3000 metres on the track. •••Energy system contribution to 1500- and 3000-metre track running

The results were conclusive. Even at a distance as short as 1500 metres 77% (men) and 86% (women) of the energy expenditure was aerobic. Over 3000 metres those numbers increased to 86% and 94% respectively.

Given that we now know that the relative importance of the aerobic energy system increases with distance, the conclusion is obvious: You cannot overstate the importance of aerobic condition as it relates to long-distance running.

How To Improve Your Aerobic Capacity

If you read the first paragraph, you already know the answer. The most efficient way to improve your aerobic capacity is to run at an easy to moderate pace. And you need to do it regularly and consistently over time.

There are no shortcuts to speed up the physiological adaptions that turn you into an endurance monster. To the contrary, running too fast will diminish aerobic adaption after a run.

The Aerobic Threshold

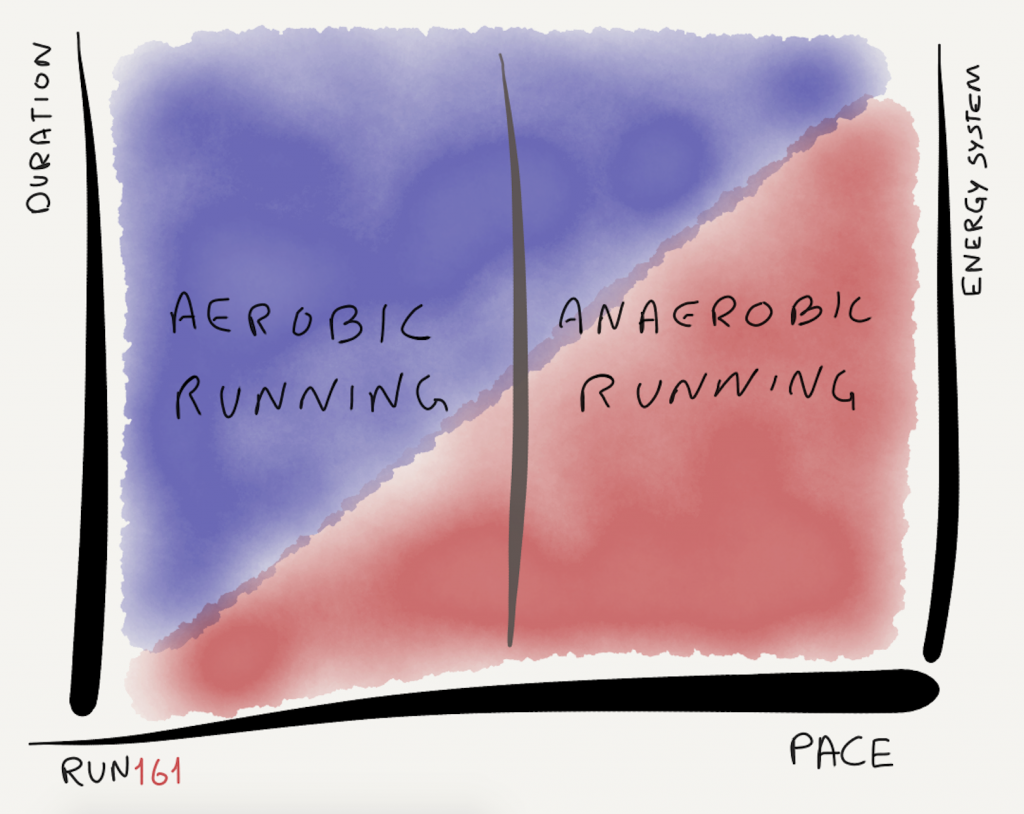

Key to understanding the upper-intensity limit of an aerobic run is the aerobic threshold. We can illustrate this by adding a line to the chart we previously investigated.

When we fuel our running primarily with the aerobic system, we are doing aerobic running. When we cross over to the right side, the body can’t process enough oxygen to generate movement, and carbohydrate “rocket fuel” becomes increasingly important. This tipping point is known as the aerobic threshold.

Now, let’s reintroduce the pace-duration chart and see how it fits in with the energy systems in the background.

The highlighted point on the pace-duration curve is the pace and intensity of training that corresponds to the aerobic threshold for one particular runner. As we can see from the curve, the runner can maintain speeds slower than the aerobic threshold for hours and hours. Conversely, time to exhaustion decreases rapidly beyond this threshold, as the anaerobic energy system is engaged to sustain the effort.

To get an accurate measure of your aerobic threshold pace, you need to get a metabolic test on a treadmill in a lab. However, even the most committed runners can get a sufficiently precise estimate through more straightforward means.

Perceived Effort of Aerobic Threshold

The simplest method to make sure you are running within the aerobic intensity sone is to be aware of your breathing. Once your breathing becomes laboured, you are training too hard. If you run with friends — or like to converse with yourself — the talking test gives additional input. You should be able to hold a normal conversation without pauses on account of your running while in the aerobic zone of intensity.

Aerobic Threshold and Heart Rate

Heart rate offers more precise feedback for controlling your running intensity, compared to perceived effort. Particularly for less experienced runners, wearing a heart rate strap can be useful to calibrate your perception of effort. It can be challenging not to let your intensity drift above the aerobic threshold. Especially on days where you are feeling good, and running fast feels comfortable,

For most runners, their aerobic intensity zone is between 70% and 80% of max heart rate, as per Pfitzinger’s Advanced Marathoning. Where you’re running within this interval is of lesser importance. The cumulative load of your training plan and life, in general, will influence how you’re feeling on the day. Stay within the recommended zone, and you are giving the body the desired stimulus for improvement.

Pace Limits of Aerobic Threshold

You can also use race performances to estimate the limits of your aerobic training paces. Using the VDOT framework, the upper bounds of the “easy” training pace is around your aerobic threshold pace. In my personal experience, this corresponds well to the heart rate-based approach on most days.

Pfitzinger suggests a more straightforward method. If you know your marathon race pace, he suggests that you should run your aerobic runs between 15 to 25% slower. In other words, if your marathon pace is 4 minutes (240 seconds) per kilometre, the range for your aerobic runs is between 4:36 (276 seconds) and 5:00 (300 seconds) per km.

It’s important to note that the goal of your aerobic runs in not to maximise time around your aerobic threshold as possible. Instead, these runs should be by feel, and the aerobic threshold should be the upper-intensity limit of these runs.

The exact intensity that is “right” compared your aerobic threshold will vary depending on a multitude of factors, such as total running volume, running history. Outside factors such as work or family stress will also play a role.

As a general rule of thumb, however, your aerobic runs should not interfere with your quality sessions. If you find that you are tired the day after an aerobic run, you are running too fast and need to back off a bit.

How Much of My Running Should Be Aerobic?

There is no one exact percentage of your running that should be within the aerobic range. The correct number will depend on factors such as your running history and aerobic capacity and periodisation of training.

The less experienced you are as a runner, the more you’ll gain from focusing on developing your aerobic capacity. Variety in training is essential, however. Even your base building phase should include elements such as strides, hills repetitions and light workouts.

Regardless of how experienced you are as a runner, the aerobic work should always make up the bulk of your running. Depending on volume, if more than 20% (high mileage mileage) to 40% (low mileage) of your running is faster than your aerobic threshold, you are asking for trouble. And what is more, you are leaving easy fitness gains on the table.

Like this?

Let me know by sending me an email at lc@run161.com.